New Delhi (NVI): The world’s biggest iceberg is on a collision course with a remote South Atlantic island that is home to thousands of penguins and seals, and could impede their ability to gather food.

Icebergs naturally break off from Antarctica into the ocean, but climate change has accelerated the process — in this case, with potentially devastating consequences for abundant wildlife in the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia, according to British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists.

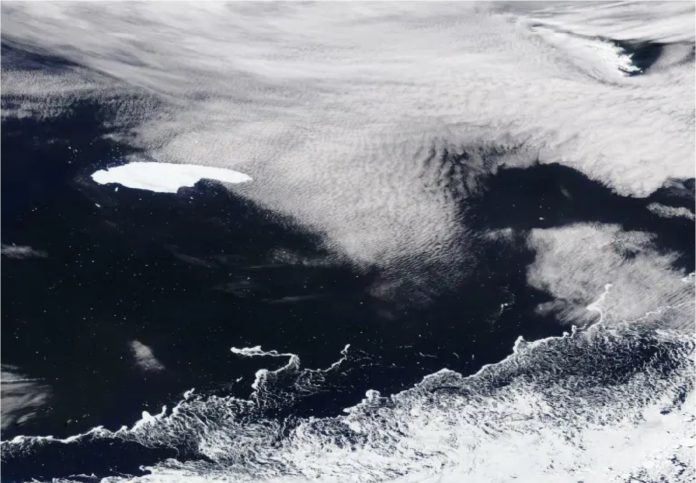

Shaped like a fist with a pointing finger, the iceberg known as A68a split off in 2017 from Larsen Ice Shelf on the West Antarctic Peninsula, which has warmed faster than any other part of the Earth’s southernmost continent.

At its current rate of travel, it will take the giant iceberg – which is several times the area of greater London – 20 to 30 days to run aground in the island’s shallow waters.

A68a is 160 kilometres (93 miles) long and 48 kilometres (30 miles) across at its widest point, but the iceberg is less than 200 metres deep, which means it could get dangerously close to the island.

“We put the odds of collision at 50/50,” Andrew Fleming from the British Antarctic Survey said.

Many thousands of King penguins – a species with a bright splash of yellow on their heads – live on the island, alongside Macaroni, Chinstrap and Gentoo penguins.

Seals also populate South Georgia, as do wandering albatrosses, the largest flying bird species.

If the iceberg runs aground near South Georgia, foraging routes could be blocked, hampering the ability of parents to feed their young, and thus threatening the survival of seal pups and penguin chicks.

Furthermore, the incoming iceberg would also crush organisms and their seafloor ecosystem, which would need decades or centuries to recover.

Carbon stored by these organisms would be released into the ocean and atmosphere, adding to carbon emissions caused by human activity, the researchers said.

However, as A68a drifted with currents across the South Atlantic, the iceberg did a great job of distributing microscopic edibles for the ocean’s tiniest creatures, said Tarling.

“Over hundreds of years, this iceberg has accumulated a lot of nutrients and dust, and they are starting to leach out and fertilise the oceans,” researchers added.

-CHK