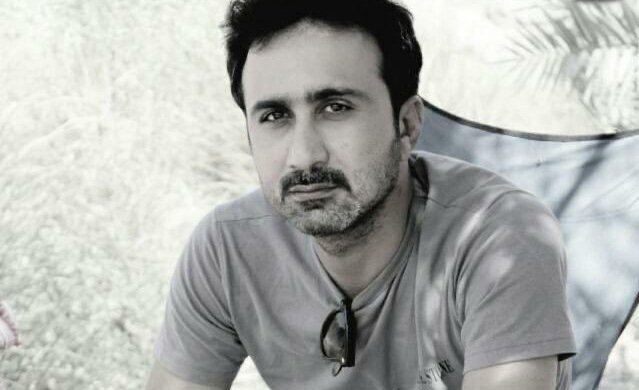

New Delhi (NVI): Sweden, which claims to be one of the safest countries in the world, has a blot on its reputation after a senior journalist from Pakistan-held Balochistan Sajid Hussain was found dead in questionable conditions, nearly two months after he went missing mysteriously.

Pakistan’s intelligence agencies are clearly suspected in the case since the 39-year-old Editor-in-Chief of Balochistan Times had sought asylum in Sweden because of fear of reprisal from the Pakistan establishment for exposing human rights violations and machinations by it in Balochistan.

Hussain was in Sweden since 2012 after fleeing from Pakistan in the wake of death threats and intimidation by police, including a raid on his home. He formally sought asylum in September 2017 in Sweden where he was recognised as a refugee.

The independent journalist disappeared on March 2 in Uppsala, suspectedly abducted by the Pakistani intelligence operatives. A case about his disappearance was registered on March 5 but for nearly two months, the Swedish police failed to locate him. On April 23, his body was found in Fyris River on the outskirts of Uppsala and on May 1, the Swedish police confirmed that it was the body of Hussain only.

After conducting an autopsy, the Swedish Police has said a crime could not be completely ruled out.

The online newspaper Balochistan Times of Hussain is known for its coverage on alleged human rights violations in Pakistan.

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Hussain went missing after boarding a train in Stockholm at around 11:30 a.m. on March 2 to go to Uppsala, for collecting the keys to his new apartment and leaving some personal effects there.

“No one has heard from him since then. His Pakistan-based wife, Shahnaz Baloch, was due to join him in Uppsala a few days later. The Swedish police told RSF that he did alight from the train in Uppsala 45 minutes after it left Stockholm,” it said.

Immediately after Hussain went missing, Erik Halkjaer, the president of RSF’s Swedish section, said, “I urge the Swedish authorities to take his disappearance seriously and investigate it thoroughly. Considering the recent attacks and harassment against other Pakistani journalists in Europe, we cannot ignore the possibility that his disappearance is related to his work.”

Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk, had said “Everything indicates that this is an enforced disappearance… And if you ask yourself who would have an interest in silencing a dissident journalist, the first response would have to be the Pakistani intelligence services.”

Bastard added, “In view of the nature of the articles published by Sajid Hussain, which often crossed the ‘red lines’ imposed by the military establishment in Islamabad, and all the other reasons for suspecting Pakistani intelligence, we urge the Swedish police to work on this hypothesis.”

Citing “confidential information” obtained by it, RSF said a list of Pakistani dissidents who are now refugees in other countries is currently circulated within Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the most powerful of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies.

RSF’s suspicion is based on similar incidents that have occurred earlier in European countries.

Ahmad Waqass Goraya, a Pakistani blogger living in self-imposed exile in the Netherlands, was attacked and threatened outside his Rotterdam home on February 2 by two individuals speaking Urdu, the RSF said. “This attack fits the modus operandi of Pakistani spy agencies,” he told RSF afterwards.

Earlier, in January 2017, Goraya was abducted and tortured in Pakistan for several weeks by a “government institution with links to the military.”

RSF has also been able to establish that at least two other Pakistani journalists with refugee status in European countries are currently being pressured by the ISI by means of intimidation of family members still in Pakistan.

Pakistan is ranked 142nd out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2019 World Press Freedom Index.

According to Malik Siraj Akbar, the Editor-in-Chief of the Baluch Hal, “The Swedish government failed in its promise to Sajid that he would be safe there.”

In a column, he has written, “It (Swedish government) should at least be honest now in sharing information about what caused his death. If he was killed, what are the Swedish authorities doing to trace his killers? For Islamabad, the question remains unchanged even after a decade: Why isn’t Baluchistan safe for its own children?”

Akbar wrote that “Nobody believed that he (Sajid) would go missing for a long time in an extremely safe place like Sweden, known for its freedoms and the rule of law. His friends and family became frustrated only after the police began to test their patience by not making any progress in tracing his whereabouts. Sajid’s furious friends equated the Swedish Police with their Pakistani counterparts in terms of their slow and inefficient work. They seemed frustrated that the police, after several weeks, could not find out where Sajid had gone and what had happened to him.

“Now that they have found him, the police have, to some extent, restored their reputation. The cops are still not telling us how Sajid died. Will we have to wait for several more weeks? Maybe.”

Akbar feels that Sajid’s death sends a grim message to other asylum-seekers that no place in the world is entirely safe. “If Jamal Khashoggi and Sajid can go missing and eventually get killed far away from their home countries, no asylum-seeker should assume that they cannot be hunted down,” the senior editor wrote.

According to him, “Pakistan’s diplomatic missions, as once reported by New York Times, regularly spy on the diaspora throughout the world, including the United States under the disguise of “community outreach.”