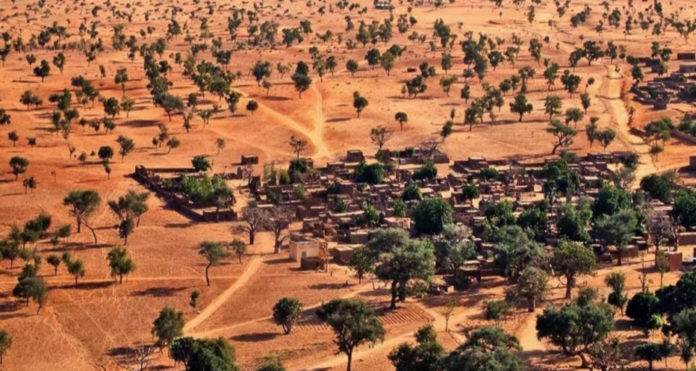

New Delhi (NVI): There are more than 1.8 billion trees and shrubs in the West African Sahara Desert, despite conceptions that the desert is a desolate wasteland, according to a new study.

The recent study published in the journal Nature—used detailed satellite imagery from NASA, and deep learning with advanced artificial intelligence (AI) method.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen counted over 1.8 billion trees in the 1.3 million square kilometer (501,933 square miles) area that covers the western-most portion of the Sahara Desert called the Sahel, along with sub-humid zones of West Africa, the World Economic Forum reported.

“We were very surprised to see that quite a few trees actually grow in the Sahara Desert, because up until now, most people thought that virtually none existed, said Martin Brandt, professor at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the study.

“We counted hundreds of millions of trees in the desert alone. Doing so wouldn’t have been possible without this technology. Indeed, I think it marks the beginning of a new scientific era,” he added.

However, the normal satellite imagery is unable to identify individual trees, they remain literally invisible.

Moreover, a limited interest in counting trees outside of forested areas led to the prevailing view that this particular region had almost no trees. This is the first time that anyone counted trees across a large dryland region.

The new knowledge about trees in dryland areas like this is important for several reasons, Brandt said, adding that, they represent an unknown factor when it comes to the global carbon budget.

“Trees outside of forested areas are usually not included in climate models, and we know very little about their carbon stocks. They are basically a white spot on maps and an unknown component in the global carbon cycle,” he added.

The new study further contributes to better understanding of the importance of trees for biodiversity and ecosystems and for the people living in these areas.

In particular, enhanced knowledge about trees is also important for developing programs that promote agroforestry, which plays a major environmental and socioeconomic role in arid regions, it added.

“Thus, we are also interested in using satellites to determine tree species, as tree types are significant in relation to their value to local populations who use wood resources as part of their livelihoods,” said Rasmus Fensholt, professor in the geosciences and natural resource management department.

“Trees and their fruit are consumed by both livestock and humans, and when preserved in the fields, trees have a positive effect on crop yields because they improve the balance of water and nutrients,” Fensholt added.

The researchers developed the deep learning algorithm that made the counting of trees over such a large area possible. They fed the deep learning model thousands of images of various trees to show it what a tree looks like.

Based on the recognition of tree shapes, the model could automatically identify and map trees over large areas and thousands of images. The model needs only hours what would take thousands of humans several years to achieve, the study said.

Furthermore, the researchers will next expand the count to a much larger area in Africa and in the longer term, they plan to create a global database of all trees growing outside forest areas, it noted.

-RJV